This post will be probably a too ambitious one, since I'm going to write about a

very theoretical aspect of computation, in particular the so called **abstract

interpretation**: for now let me just say that this field tries to give the

_best possible answer_ to unsolvable characterization of computer programs.

Another point of view that I want to address is the use of this kind of analysis

with reverse engineering, since a lot of aspects between these two kind of

analysis are shared.

This post will have pretty mathematical formalism but should be readable enough

also without a PhD.

## Languages

As a first thing to start thinking about code we need to define what is a

program: let me show you a grammar of a pseudo-C language:

$$

\begin{array} {rlll}

\mathsf{S} & ::= & \mathsf{x = A} \\\\

& | & ; \\\\

& | & \mathsf{{\bf if}\, (B)\, S} \\\\

& | & \mathsf{{\bf if}\, (B)\, S\\, {\bf else}\, S} \\\\

& | & \mathsf{{\bf while}\, (B)\, S} \\\\

& | & \mathsf{{\bf break} ; } \\\\

& | & \mathsf{\\{ Sl \\} } \\\\

\mathsf{Sl} & ::= &\mathsf{Sl}\\; \mathsf{S}\\;|\,\epsilon \\\\

\mathsf{P} & ::= &\mathsf{Sl} \\\\

\end{array}

$$

We'll use this grammar to define a **structural analysis** of the code, a

pseudo-recursive approach: to understand what I mean, let's start with the

simplest analysis possible, i.e., how many statements there are in the program;

obviously you would think that simply counting the "lines" should suffice, but

we can instead define the counting in a structural way, starting from the

terminals, i.e. the statements themselves

$$

\begin{array} {rlll}

\mathsf{S} & ::= & \mathsf{x = A} & \hbox{count}(\mathsf{S}) = 1 \\\\

\mathsf{Sl} & ::= & \mathsf{Sl}^\prime\\;\mathsf{S} & \hbox{count}(\mathsf{Sl})=\hbox{count}(\mathsf{Sl}^\prime) + \hbox{count}(\mathsf{S}) \\\\

\mathsf{S} & ::= & \mathsf{{\bf if}\\, (B)\\, S_t} & \hbox{count}(\mathsf{S}) = \hbox{count}(\mathsf{S_t}) + 1 \\\\

\mathsf{S} & ::= & \mathsf{{\bf if}\\, (B)\\, S_t\\, {\bf else}\\, S_f} & \hbox{count}(\mathsf{S}) = \hbox{count}(\mathsf{S_t}) + \hbox{count}(\mathsf{S_f}) + 2 \\\\

\mathsf{S} & ::= & \mathsf{{\bf while}\\, (B)\\, S_b} & \hbox{count}(\mathsf{S}) = \hbox{count}(\mathsf{S_b}) + 1 \\\\

\end{array}

$$

This works because since a program it's a **finite** set of statements, there are **finite** numbers of steps

to reach the terminating elements of the grammar.

Now, for something more interesting that will come in hand later, we can

associate at each structure a **control flow graph**: these diagrams show

the \\(\mathsf{\bf if}\\), \\(\mathsf{\bf if else}\\) and \\(\mathsf{\bf while}\\)

diagramatical structure

stateDiagram

head: if (B)

[*] --> head

head --> [*]

head --> S: true

S --> [*]

stateDiagram

head: if (B)

left: S

right: S

[*] --> head

head --> left: false

head --> right: true

right --> [*]

left --> [*]

stateDiagram

head: while (B)

body: S

[*] --> head

head --> body: true

body --> head

head --> [*]: false

Now, using structural analysis, it's possible to deduce that relationship between the

number of entering and exiting edges in a particular block

$$

\begin{array} {rlll}

\mathsf{S} & ::= & \mathsf{x = A} & \sharp\hbox{out}(\mathsf{S}) = 1 \\\\

\mathsf{Sl} & ::= & \mathsf{Sl}^\prime\\;\mathsf{S} & \sharp\hbox{in}(\mathsf{Sl})=\sharp\hbox{in}(\mathsf{Sl}^\prime),\;\sharp\hbox{out}(\mathsf{Sl}) = \sharp\hbox{out}(\mathsf{S}) \\\\

\mathsf{S} & ::= & \mathsf{{\bf if}\\, (B)\\, S_t} & \sharp\hbox{out}(\mathsf{S}) = \sharp\hbox{out}(\mathsf{S_t}) + 1 \\\\

\mathsf{S} & ::= & \mathsf{{\bf if}\\, (B)\\, S_t\\, {\bf else}\\, S_f} & \sharp\hbox{out}(\mathsf{S}) = \sharp\hbox{out}(\mathsf{S_t}) + \sharp\hbox{out}(\mathsf{S_f}) \\\\

\mathsf{S} & ::= & \mathsf{{\bf while}\\, (B)\\, S_b} & \sharp\hbox{out}(\mathsf{S}) = 1 \\\\

\end{array}

$$

and in particular it's obvious that the convergence node of an \\(\mathsf{\bf if}\\)

block might have a number of entering edges without an upper bound.

**Note:** you can build directly the flowchart from the CFG.

With this we can assume that the final CFG is composed of nodes that have **at

most** two exiting edges but an unlimited number of entering edges.

But, the important fact is that the control flow instructions are the ones with

the two exiting edges, where the ``while`` is identifiable by a returning edge

but the ``if`` is recognizable from the two different paths converging to the

same exit node. Obviously ``goto`` are not take into consideration, but in our

case it's not part of the language.

## Abstract interpretation and lattices

What is abstract interpretation and why we should care? to answer this you

should know that from theoretical computation studies it's known that it's

impossible to build a program that is able to extract information of another

program unless it's a trivial property.

This doesn't mean that we cannot know anything about a given program, simply

that we must accept the fact the we have to approximate something.

The following in this section is an overview of the formalism needed to actually

talk about what means "approximate". It's pretty much taken from two books: the

most formal book on the subject "Principles of abstract interpretation" by

Patrick Cousot (if you are not a math-person avoid it, it's practically a book

about proving theorems) and "Static program analysis" by Anders Møller and Michael I. Schwartzbach,

an openly available book that you can find [here](https://cs.au.dk/~amoeller/spa/spa.pdf).

The last one is more accessible (it's still pretty formal though).

Let's start with the simplest of the examples (it's the first example in any

book about this stuff :P) i.e. the study of the "sign": we know that a variable

representing an integer can assume three possible values with respect to the

sign, it can be positive, negative or be zero.

With repect to multiplication this "classification" behaves well

$$

\begin{array} {r|ccc}

* & + & 0 & - \\\\

\hline + & + & 0 & - \\\\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\\\

- & - & 0 & + \\\\

\end{array}

$$

but not the addition

$$

\begin{array} {r|ccc}

+ & + & 0 & - \\\\

\hline + & + & + & ? \\\\

0 & + & 0 & - \\\\

- & ? & - & - \\\\

\end{array}

$$

since summing two integers with opposite signs can have **all** the prossible

outcomes, this means that we lose **any information possible**. Moreover this

means that every further calculation needs to take that into account (note how

in the particular case of multiplication, whatever value is multiplied by zero,

it becomes zero).

To formalize mathematically this concept of "anything" we introduce the symbol

\\(\top\\) (you can read it as "top") representing the set of all possible values

in this representation (we are talking about signs, so it's the set

\\(\\{+,0,-\\}\\)) that roughly speaking means "I don't know what value actually

is". Let's also introduce the symbol \\(\bot\\) (you can read it as "bottom") to

indicate values that are not numbers (think about pointers or unreachable

variables).

This allows us to formalize our reasoning defining an **abstract domain**

composed by five symbols \\(\\{+, 0, -, \top, \bot\\}\\) that we can arrange in

the following manner

$$

\begin{matrix}

&& \top & \\\\

&\huge\diagup & \huge| & \huge\diagdown \\\\

+ & & 0 & & -\\\\

&\huge\diagdown & \huge| & \huge\diagup \\\\

&&\bot

\end{matrix}

$$

where the elements are ordered vertically with regard of "approximation";

let's define an ordering via the operator \\(\sqsubseteq\\):

when \\(x\sqsubseteq y\\) we say that \\(y\\) is a **safe approximation** of

\\(x\\), or that \\(x\\) is **at least as precise** as \\(y\\). In this case we

have \\(+\sqsubseteq\top\\). A set with such operator is called **poset**

(Partial order set). Let me introduce this space:

**Posets:** a _poset_ \\(\langle\mathbb{P}\sqsubseteq\rangle\\) is a set

\\(\mathbb{P}\\) with a _partial order_ \\(\sqsubseteq\\) that is

- _Reflexive:_ \\(\forall x\in\mathbb{P}.x\sqsubseteq x\\)

- _Antisymmetric:_ \\(\forall x,y\in\mathbb{P}.\left((x\sqsubseteq y)\wedge(y\sqsubseteq x)\right)\Rightarrow(x = y)\\)

- _Transitive:_ \\(\forall x,y,z\in\mathbb{P}.\left((x\sqsubseteq y)\wedge(y\sqsubseteq z)\right)\Rightarrow(x \sqsubseteq z)\\)

**Note:** not every couple of elements are supposed to have a well defined

relation with respect to the operator \\(\sqsubseteq\\): if for a couple of

element \\(x,y\in\mathbb{P}\\) we have \\(x\sqsubseteq\\) or \\(y\sqsubset x\\)

we say that are _comparable_, otherwise they are _incomparable_. When in a poset

all the elements are comparable we have a poset that is _total_.

Let \\(\langle \mathbb{P}, \sqsubseteq\rangle\\) be a poset and \\(S\in

\wp(\mathbb{P})\\) be a subset.This subset \\(S\\) has

- upper bound \\(u\\) iff \\(u\in\mathbb{P}\\) and \\(\forall x\in

S.x\sqsubseteq u\\)

- a least upper bound (lub, indicated \\(\sqcup S\\)) iff \\(\sqcup S\\) is an

upper bound of \\(S\\) smaller than other upper bound of \\(S\\).

\\(\sqcup\\{x, y\\}\\) is denoted with the infix notation \\(x\sqcup y\\)

The intuition around posets is that they abstract **set theory**, where

\\(\sqsubseteq\\) is the analogous of \\(\subseteq\\) and \\(\sqcup\\),

\\(\sqcap\\) have as "dual" \\(\cup\\) and \\(\cap\\).

Finite posets \\(\langle \mathbb{P}, \sqsubseteq\rangle\\) can be represented by **Hassle

diagrams**, which is a set of points \\(\\{p_x | x\in P\\}\\) in the plan such

that

- if \\(x \sqsubset y\\) then \\(p_x\\) is strictly below \\(p_y\\) and

- \\(p_x\\) and \\(p_y\\) are linked by a segment when \\(x \lessdot y\\)

(\\(y\\) covers \\(x\\)) where \\(x\lessdot y \triangleq x\sqsubset y\wedge

\not\exists z\in P.x\sqsubset z\wedge z\sqsubset y\\).

**Note:** two unlinked elements are incomparable.

$$

\begin{array}{ccl}

x\sqcap x = x & x\sqcup x = x & \hbox{idempotency} \\\\

x\sqcap y = y \sqcap x & x\sqcup y = y \sqcup x & \hbox{commutativity} \\\\

x\sqcap (y\sqcap z) = (x\sqcap y)\sqcap z & x\sqcup (y\sqcup z) = (x\sqcup y)\sqcap z & \hbox{associativity} \\\\

(x\sqcap y)\sqcup x = x & (x\sqcup y)\sqcap x = x & \hbox{absorpsion} \\\\

\end{array}

$$

**soundness:** the results are always correct

**completeness:** all true facts are provable

Soundness (\\(\Longleftarrow\\)) states that if a statement is proved bythe proof method then that

statement is true. Completeness (\\(\Longrightarrow\\)) states that the proof method is always applicable

to prove a true statement.

If you think it's useless stuff, you know, vulnerabilities come from it

- [Step-by-Step Walkthrough of CVE-2022-32792 - WebKit B3ReduceStrength Out-of-Bounds Write](https://starlabs.sg/blog/2022/09-step-by-step-walkthrough-of-cve-2022-32792/)

$$

\require{AMScd}

\begin{CD}

A @>a>> B\\\\

@V b V V @VV c V\\\\

C @>>d> D

\end{CD}

$$

### Properties

Properties can be understood as the set of mathematical objects that have this

property, e.g

$$

2\mathbb{Z} = \left\\{x\in\mathbb{Z}\,\|\,\exists k\in\mathbb{Z}.x=2k\right\\}

$$

hence if \\(P\\) is a property then \\(x\in P\\) means "\\(x\\) has property

\\(P\\)".

Under this interpretation, **logical implication** is _subset inclusion_: as an

example

$$

\hbox{"to be greater than 42 implies to be positive"} \Longleftrightarrow

\\{x\in\mathbb{Z}\,\|\,x\gt42\\}\subseteq\\{x\in\mathbb{Z}\,\|\,x\geq0\\}

$$

In the expression \\(P\subseteq Q\\), \\(P\\) is said to be **stronger**/**more

precise** since its property is satisfied by **less elements**.

To refer to the abstract domain of sign, we can associate to each abstract sign

a set represented by the elements in \\(\mathbb{Z}\\) that have such property,

i.e.

$$

\lt \,\sim\,\\{x\in\mathbb{Z}\,\|\,x\lt0\\}

$$

Another example is the property to be an integer constant, that is espressed by

the set

$$

\left\\{\left\\{ n\right\\}\,\|\,n\in\mathbb{Z}\right\\}

$$

### Liveness and safeness properties

There are two properties that are fundamental:

- **liveness:** something "good" must happen during execution

- **safeness:** anything "bad" doesn't happen during execution

Let me borrow an example from the seminal paper that defined these concepts,

using a **producer**/**consumer**:

it consists of a producer process which puts messages into a buffer and a

consumer process which removes the messages. We assume that the buffer can

hold at most \\(b\\) messages, \\(b\qeq1\\). The processes must be

synchronized so the producer doesn't try to put a message into a buffer if

there is no room for it, and the consumer doesn't try to remove a message

that has not yet been produced

Let's implement these entities using a buffer \\(B\\) of dimension \\(b\\) using as

references respectively to the sent and received messages with the variables

\\(s\\) and \\(r\\): when a producer wants to send a message it puts it into

\\(B[s\mod b]\\) and the consumers takes it from \\(B[r \mod b]\\).

```

while (1) {

while ((s - r) % b == 0 && r != s)

;

send_message(s);

s = s + 1;

}

```

The following diagrams explain the cfg of producer and consumer:

stateDiagram-v2

main: while (1)

head: s - r mod b = 0 and r != s

message: deliver message

cursor: s = s + 1

[*] --> main

main --> head

head --> message: false

message --> cursor

cursor --> main

head --> head: true

stateDiagram-v2

main: while (1)

head: s - r mod b = 0 and r == s

message: receive message

cursor: r = r + 1

[*] --> main

main --> head

head --> message: false

message --> cursor

cursor --> main

head --> head: true

Now, we define \\(n = s - r\\) as the number of messages in the buffer, to prove

the desired safety property we need to prove that \\(0\leq n\leq b\\) holds for

the execution of the entire program. Here program is the combined execution of

these two processes.

An **assertion** is a logical function of program variables and tokens positions

and it's said to be **invariant** if it's always true during the execution of

the program.

An **interpretation** of a program is an assignment of an assertion to each arc

of the cfg. We say that the program is in a **legitimate state** if each token

is on an arc whose interpretation is true. The interpretation is said to be

**invariant** if the program always remains in a legitimate state throughout its

execution.

So, under these definitions, proving the program correctness can be done

verifying the following conditions:

1. the program starts in a legitimate state

2. during execution it remains in a legitimate state, i.e. if at a certain

moment it's in a legitimate state, any execution step will leave it in a

legitimate state.

### Turing my beloved

Assume \\(\hbox{termination}(P)\\) would always terminate and returns true iff

\\(P\\) always terminates on all input data; the following statement is a

contradiction

$$

P = \mathsf{\bf while}(\hbox{termination}(P));

$$

### Structural deductive stateless prefix trace semantics

This is from chapter 6 of PoAI;

- **Stateless:** does not register the values of variables

- **Structural:** by induction on the program syntax

- **Deductive:** the semantics of each program component is specified by a

deductive system of axioms and rules of inference, a program execution being

a proof in such a system.

\\(\def\trace{\mathbb{T}}\\)

A **trace** is a finite sequence of configurations (labels) separated by

actions. We let \\(\trace^+\\) be the set of finite traces, \\(\trace^\infty\\)

be the set of infinite traces and

\\(\trace^{+\infty}\buildrel\triangle\over=\trace^+\cup\trace^\infty\\)

\\(\def\action#1{\xrightarrow{\hspace{1cm}\displaystyle{#1}\hspace{1cm}}}\\)

\\(\def\l#1{\vphantom{x}^{#1}}\\)

\\(\def\pijoin{\buildrel\frown\over\cdot}\\)

$$

\pi_1\l{l_1}\pijoin\l{l_2}\pi_2=\cases{

\pi_1\l{l_1}\pi_2 \,\hbox{when}\,\l{l_1}=\l{l_2}\cr

\hbox{undefined when }\,\l{l_1}\not=\l{l_2}\cr

}

$$

$$

\action{\pi_1}\underbrace{\hbox{at}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\action{\pi_2}l}_{\displaystyle\in\mathcal{S}^\star[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\left( \pi_1\hbox{at}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!] \right)}

$$

Because \\(\mathbb{T}\longrightarrow\wp(\mathbb{T^\star})\\) is isomorph to

\\(\wp(\mathbb{T}^+\times\mathbb{T}^\star)\\) then we can write

$$

\mathcal{S}^{\hat\star}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!] = \left\\{\langle\pi,\pi^\prime\rangle\,\|\,\pi\in\trace^+\wedge\pi^\prime\in\mathcal{S}^\star[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\pi\right\\}

$$

so that \\(\mathcal{S}^{\star}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\\) is the right image of \\(\mathcal{S}^{\hat\star}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\\)

### Maximal trace semantics

A trace is **maximal** when it's finite and represents an execution that

terminates or it is infinite and represents an execution that doesn't terminate.

Maximal finite traces of statements are prefix executions that exit the

statement.

$$

\mathcal{S}^{\infty}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\left( \pi^l \right) \buildrel\triangle\over= \lim\left( \mathcal{S}^{\star}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\left( \pi^l \right) \right)

$$

$$

\mathcal{S}^{+}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\left(\pi_1\hbox{at}[ \\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\right)

\buildrel\triangle\over= \left\\{ \pi^{\phantom{2}l}_2\in\mathcal{S}^{\star}\[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!\](\pi_1\hbox{at}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!])\,\|\,

\vphantom{\pi}^l=\hbox{after}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\vee\left(\hbox{escape}[\\![S]\\!] \wedge\vphantom{\pi}^l=\hbox{break-to}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\right)

\right\\}

$$

$$

\eqalign{

\mathcal{S}^{+\infty}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\left(\pi^l\right) & \buildrel\triangle\over= \mathcal{S}^{+}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\left(\pi^l\right) \cup \mathcal{S}^{\infty}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\left(\pi^l\right) \\\\

\mathcal{S}^{+\infty}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\Pi & \buildrel\triangle\over= \bigcup\left\\{ \mathcal{S}^{+\infty}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\left(\pi^l\right) \, \| \, \pi^l\in\Pi \right\\} \\\\

\mathcal{S}^{+\infty}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!] & \buildrel\triangle\over= \mathcal{S}^{+\infty}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\left( \mathbb{T}^+ \right) \\\\

\mathcal{S}^{+\infty}[\\![\mathsf{P}]\\!] & \buildrel\triangle\over= \mathcal{S}^{+\infty}[\\![\mathsf{S}]\\!]\left( \left\\{ \hbox{at}[\\![\mathsf{P}]\\!] \right\\}\right) \\\\

}

$$

## Subroutines

In our syntax is not included explicitely the execution of subroutine but this

should not be a problem since you can think of that as a sub-CFG implictily

defined by that instruction.

## CFG from instructions

In a more abstract sense some code is a sequence of instructions, in this

context I'm going to talk about **binary** code, i.e. code that is usually

represented and stored via bits and organized in a flat way.

To clarify: in general the following argument could apply also to source code

(in particular control flow and stuff) but it's a little more complex since

allow for nesting and it's explicit about the "intended" code, but here I'm more

interested in reconstructing it. Moreover, the compiler is doing in reverse what

in general a decompiler is trying to do.

The core point here is that, being the instructions laid out one after the

other, some of them must handle the control flow and these are the instructions

we are interested in studying, at least as appetizer: let's organize the

instruction based on their behaviour with respect to control flow

- **standard:** the large majority of instructions flow to the next instruction

- **jump:** unconditional jump

- **branch:** conditional jump if some condition holds, otherwise fallthrough

- **call:** invokes a function

- **return:** transfer back control to the caller

**Note:** we can create a taxonomy for classes of instructions, first with the

subdivision "standard"/"control flow", then the latter can be subdivided again

in "intra"/"extra"-procedural, where ``call``s and ``return``s create a

_context_ that is not present with ``jmp``s and ``branch``es.

If we abstract each instruction as a vertex and we set directed edges between

an instruction and its (possible) successors we obtain what is called a

**control flow graph** (CFG from now on), this is the next step after having

disassembled your code.

Take in mind that usually the analysis is done at function level, if you

encounter a ``call`` instruction, you treat it like a ``standard`` one, if you encounter

a ``return`` instruction you set the corresponding vertex as an end point.

Two particular vertices are the **entry point** and the **exit**, the first is

usually not explicitely indicated in binary code and it's a challenging problem

by itself to find it, the latter is usually represented by the ``return`` instruction.

Calling functions is not usually included in the CFG, that generates another

graph of its own, the **call graph**.

**Note:** obviously in real code you can have **signals** and **exceptions** or

**interrupts** that go against this reasoning.

**Note:** there are cases where a stream of bytes can have different

interpretation regarding the instructions in it, I'm looking at you ``x86``. In

particular, a jump can reach in the "middle" of another possible instruction

creating a different interpretation.

It's possible to transform a little the graph, grouping instructions in regions

having a single entry point and a single exit point: the so called **basic

blocks**.

The first instruction in them is named leader, the last instruction is the

tail. The leader is either the first instruction in a program, the target of a

jump, branch or call, or the fall-through instruction of a non-taken branch.

Instructions of type jump, branch, call and return cannot be followed by any

other instruction in a block.

So at the end, basic blocks are blocks of instructions connected by branches and

are a less grained representation of a CFG; loops are obvious in such representation.

## Intermediate language

But there is much more: in the last [post about reversing ``C++`` code with

``ghidra``](link://slug/reversing-c++-qt-applications-using-ghidra) I also

talked about the capabilities of the tools to "abstract away" the actual

instructions and via ``Pcode`` that is an intermediate language used by

``ghidra`` to have a common language for all the architecture it understands.

A lot of tools have an **intermediate language** (``IL``) or **intermediate

representation** (``IR``) used for their own purposes and here I'm talking about

tools that are not even reverse engineering tools: for example

- ``LLVM``

- ``Binary Ninja``

- ``radare2``

- ``IDA``

Whatever language you use to encode the binary instructions, exists a

representation the in invariant and that is used to extract core information

about the flow of execution.

### P-code

It uses definition in ``SLEIGH``, it's human readable; ``P-code`` is a Register

Transfer Language: each native instruction is translated in (possibly) multiple

p-code operations that takes parts of the processor state as input and output

variables (so called ``Varnode``s).

The p-code obtained from direct translation is referred to as **raw** but can be

further refined and exist additional operations that are not available

initially.

Take in mind that all p-code operations are associated with the address of the

original instruction they were translated from. For a single instruction, a

counter is used to enumerate the multiple p-code operations involved in the

translation. The address and this counter, as a pair, are referred with the name

of **sequence number**.

The core p-code defined are the following ([here the documentation](https://spinsel.dev/assets/2020-06-17-ghidra-brainfuck-processor-1/ghidra_docs/language_spec/html/pcoderef.html))

| Name | Arguments | Description |

|----------|-------------------|--------------------|

| ``COPY`` | ``input0 output`` | ``output = input`` |

| ``LOAD`` | ``input0 input1 output`` | ``output = *input`` or ``output = *[input0]input1`` |

| ``STORE`` | ``input0 input1 input2`` | ``*input1 = input2`` or ``*[input0] = input2`` |

| ``BRANCH`` | ``input0`` | ``goto input0`` |

| ``CBRANCH`` | ``input0 input1`` | ``if (input1) goto input0`` |

| ``BRANCHIND`` | ``input0`` | ``goto [input0]`` |

| ``CALL`` | ``input0 ...`` | ``call [input0]`` |

| ``CALLIND`` | ``input0 ...`` | ``call [input0]`` |

| ``RETURN`` | ``input0 ...`` | ``return [input0]`` |

```

PUSH RBP

(unique, 0xea00, 8) = COPY (register, 0x28, 8)

(register, 0x20, 8) = INT_SUB (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x8, 8)

STORE (const, 0x1b1, 8), (register, 0x20, 8), (unique, 0xea00, 8)

MOV RBP,RSP

(register, 0x28, 8) = COPY (register, 0x20, 8)

SUB RSP,0x20

(register, 0x200, 1) = INT_LESS (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x20, 8)

(register, 0x20b, 1) = INT_SBORROW (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x20, 8)

(register, 0x20, 8) = INT_SUB (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x20, 8)

(register, 0x207, 1) = INT_SLESS (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x0, 8)

(register, 0x206, 1) = INT_EQUAL (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x0, 8)

(unique, 0x12e80, 8) = INT_AND (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0xff, 8)

(unique, 0x12f00, 1) = POPCOUNT (unique, 0x12e80, 8)

(unique, 0x12f80, 1) = INT_AND (unique, 0x12f00, 1), (const, 0x1, 1)

(register, 0x202, 1) = INT_EQUAL (unique, 0x12f80, 1), (const, 0x0, 1)

MOV dword ptr [RBP + local_1c],EDI

(unique, 0x3100, 8) = INT_ADD (register, 0x28, 8), (const, 0xfffffffffff

(unique, 0xbf00, 4) = COPY (register, 0x38, 4)

STORE (const, 0x1b1, 4), (unique, 0x3100, 8), (unique, 0xbf00, 4)

MOV qword ptr [RBP + local_28],RSI

(unique, 0x3100, 8) = INT_ADD (register, 0x28, 8), (const, 0xfffffffffff

(unique, 0xc000, 8) = COPY (register, 0x30, 8)

STORE (const, 0x1b1, 4), (unique, 0x3100, 8), (unique, 0xc000, 8)

MOV RAX,qword ptr [RBP + local_28]

(unique, 0x3100, 8) = INT_ADD (register, 0x28, 8), (const, 0xfffffffffff

(unique, 0xc000, 8) = LOAD (const, 0x1b1, 4), (unique, 0x3100, 8)

(register, 0x0, 8) = COPY (unique, 0xc000, 8)

ADD RAX,0x8

(register, 0x200, 1) = INT_CARRY (register, 0x0, 8), (const, 0x8, 8)

(register, 0x20b, 1) = INT_SCARRY (register, 0x0, 8), (const, 0x8, 8)

(register, 0x0, 8) = INT_ADD (register, 0x0, 8), (const, 0x8, 8)

(register, 0x207, 1) = INT_SLESS (register, 0x0, 8), (const, 0x0, 8)

(register, 0x206, 1) = INT_EQUAL (register, 0x0, 8), (const, 0x0, 8)

(unique, 0x12e80, 8) = INT_AND (register, 0x0, 8), (const, 0xff, 8)

(unique, 0x12f00, 1) = POPCOUNT (unique, 0x12e80, 8)

(unique, 0x12f80, 1) = INT_AND (unique, 0x12f00, 1), (const, 0x1, 1)

(register, 0x202, 1) = INT_EQUAL (unique, 0x12f80, 1), (const, 0x0, 1)

MOV RAX,qword ptr [RAX]

(unique, 0xc000, 8) = LOAD (const, 0x1b1, 4), (register, 0x0, 8)

(register, 0x0, 8) = COPY (unique, 0xc000, 8)

MOV RDI,RAX

(register, 0x38, 8) = COPY (register, 0x0, 8)

CALL ::atoi

(register, 0x20, 8) = INT_SUB (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x8, 8)

STORE (const, 0x1b1, 8), (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x10117b, 8)

CALL (ram, 0x101050, 8)

MOV dword ptr [RBP + index],EAX

(unique, 0x3100, 8) = INT_ADD (register, 0x28, 8), (const, 0xfffffffffff

(unique, 0xbf00, 4) = COPY (register, 0x0, 4)

STORE (const, 0x1b1, 4), (unique, 0x3100, 8), (unique, 0xbf00, 4)

MOV EAX,dword ptr [RBP + index]

(unique, 0x3100, 8) = INT_ADD (register, 0x28, 8), (const, 0xfffffffffff

(unique, 0xbf00, 4) = LOAD (const, 0x1b1, 4), (unique, 0x3100, 8)

(register, 0x0, 4) = COPY (unique, 0xbf00, 4)

(register, 0x0, 8) = INT_ZEXT (register, 0x0, 4)

CMP EAX,0x2

(register, 0x200, 1) = INT_LESS (register, 0x0, 4), (const, 0x2, 4)

(register, 0x20b, 1) = INT_SBORROW (register, 0x0, 4), (const, 0x2, 4)

(unique, 0x29000, 4) = INT_SUB (register, 0x0, 4), (const, 0x2, 4)

(register, 0x207, 1) = INT_SLESS (unique, 0x29000, 4), (const, 0x0, 4)

(register, 0x206, 1) = INT_EQUAL (unique, 0x29000, 4), (const, 0x0, 4)

(unique, 0x12e80, 4) = INT_AND (unique, 0x29000, 4), (const, 0xff, 4)

(unique, 0x12f00, 1) = POPCOUNT (unique, 0x12e80, 4)

(unique, 0x12f80, 1) = INT_AND (unique, 0x12f00, 1), (const, 0x1, 1)

(register, 0x202, 1) = INT_EQUAL (unique, 0x12f80, 1), (const, 0x0, 1)

JBE LAB_0010119c

(unique, 0xca00, 1) = BOOL_OR (register, 0x200, 1), (register, 0x206, 1)

CBRANCH (ram, 0x10119c, 8), (unique, 0xca00, 1)

LEA RAX,[s_forbidden!_0010200d]

(register, 0x0, 8) = COPY (const, 0x10200d, 8)

MOV RDI=>s_forbidden!_0010200d,RAX

(register, 0x38, 8) = COPY (register, 0x0, 8)

CALL ::puts

(register, 0x20, 8) = INT_SUB (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x8, 8)

STORE (const, 0x1b1, 8), (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x101195, 8)

CALL (ram, 0x101030, 8)

MOV EAX,0x1

(register, 0x0, 8) = COPY (const, 0x1, 8)

JMP LAB_001011d0

BRANCH (ram, 0x1011d0, 8)

MOV EAX,dword ptr [RBP + index]

(unique, 0x3100, 8) = INT_ADD (register, 0x28, 8), (const, 0xfffffffffff

(unique, 0xbf00, 4) = LOAD (const, 0x1b1, 4), (unique, 0x3100, 8)

(register, 0x0, 4) = COPY (unique, 0xbf00, 4)

(register, 0x0, 8) = INT_ZEXT (register, 0x0, 4)

CDQE

(register, 0x0, 8) = INT_SEXT (register, 0x0, 4)

LEA RDX,[RAX*0x8]

(unique, 0x3680, 8) = INT_MULT (register, 0x0, 8), (const, 0x8, 8)

(register, 0x10, 8) = COPY (unique, 0x3680, 8)

LEA RAX,[messages]

(register, 0x0, 8) = COPY (const, 0x104030, 8)

MOV RAX=>messages,qword ptr [RDX + RAX*0x1]

(unique, 0x3300, 8) = INT_MULT (register, 0x0, 8), (const, 0x1, 8)

(unique, 0x3400, 8) = INT_ADD (register, 0x10, 8), (unique, 0x3300, 8)

(unique, 0xc000, 8) = LOAD (const, 0x1b1, 4), (unique, 0x3400, 8)

(register, 0x0, 8) = COPY (unique, 0xc000, 8)

MOV RSI,RAX

(register, 0x30, 8) = COPY (register, 0x0, 8)

LEA RAX,[s_message:_'%s'_00102018]

(register, 0x0, 8) = COPY (const, 0x102018, 8)

MOV RDI=>s_message:_'%s'_00102018,RAX

(register, 0x38, 8) = COPY (register, 0x0, 8)

MOV EAX,0x0

(register, 0x0, 8) = COPY (const, 0x0, 8)

6_c32105f2

CALL ::printf

(register, 0x20, 8) = INT_SUB (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x8, 8)

STORE (const, 0x1b1, 8), (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x1011cb, 8)

CALL (ram, 0x101040, 8)

MOV EAX,0x0

(register, 0x0, 8) = COPY (const, 0x0, 8)

LEAVE

(register, 0x20, 8) = COPY (register, 0x28, 8)

(register, 0x28, 8) = LOAD (const, 0x1b1, 8), (register, 0x20, 8)

(register, 0x20, 8) = INT_ADD (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x8, 8)

RET

(register, 0x288, 8) = LOAD (const, 0x1b1, 8), (register, 0x20, 8)

(register, 0x20, 8) = INT_ADD (register, 0x20, 8), (const, 0x8, 8)

RETURN (register, 0x288, 8)

```

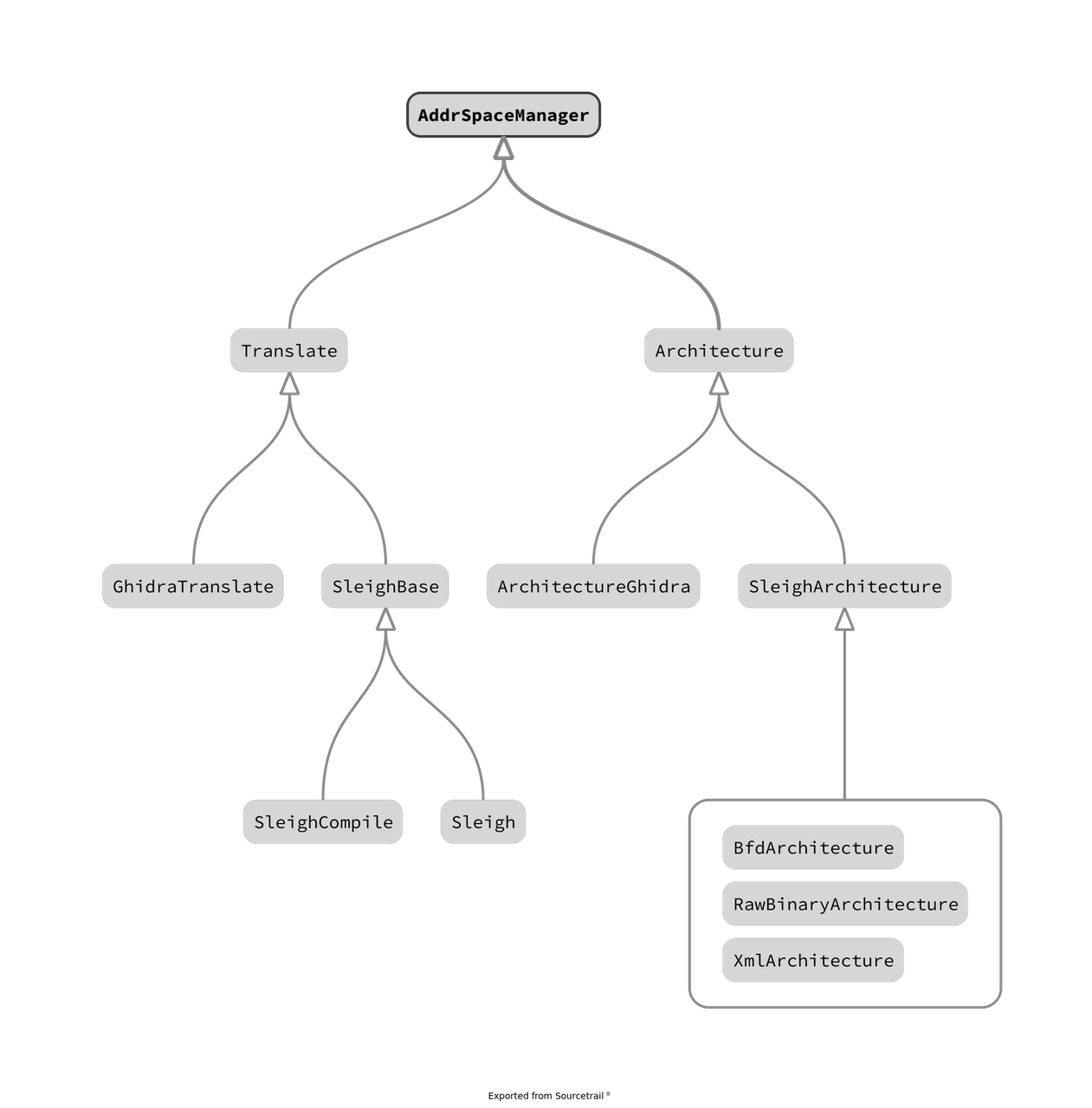

## Ghidra's decompiler implementation

On Debian gradle is at version 4 but it requires version 7 :P

https://github.com/NationalSecurityAgency/ghidra/blob/master/DevGuide.md

export PATH=/opt/gradle-7.5.1/bin:$PATH

export JAVA_HOME=$(readlink -f /usr/bin/javac | sed "s:/bin/javac::")

be sure to have openjdk17

These are my personal notes about the implementation of the decompiling process in ``ghidra``,

it's not authoritative and could be all a fever dream from my side, take it with

a grain of salt.

First of all, ``ghidra`` is built using two different languages, ``C++`` for the

core analysis and ``Java`` for firther manipulation and the application itself:

user interface, plugins etc...

The decompiler it's written in ``C++``, it's possible to compile it separately

using the following encantation

```

$ cd Ghidra/Features/Decompiler/src/decompile/cpp

$ make decomp_dbg

$ export SLEIGHHOME=~/git/ghidra/

$ ./decomp_dbg

[decomp]>

```

but ``ghidra`` itself calls it via the ``DecompInterface`` class that in reality

uses a client in ``C++`` located at ``Ghidra/Features/Decompiler/src/decompile/cpp/ghidra_process.cc``

that registers the following commands

- ``registerProgram``

- ``deregisterProgram``

- ``flushNative``

- ``decompileAt``: decompile a specific function

- ``structureGraph``

- ``setAction``

- ``setOptions``

(if you want to know more details you can look at the source code that has a lot

of comments); you can find [here](https://github.com/NationalSecurityAgency/ghidra/blob/6842712129b8da45077bb8c5049e607d685f4dea/Ghidra/Features/Decompiler/src/main/java/ghidra/app/decompiler/DecompInterface.java#L748)

where it calls ``decompileAt``

The communication is done via ``XML`` with the actual decompiler process that is implemented

``Ghidra/Features/Decompiler/src/decompile/cpp/ghidra_process.cc`` is the client

The actual binary is named ``decompile`` (at ``./Ghidra/Features/Decompiler/build/os/linux_x86_64/decompile``)

the command line decompiler is implemented in

``Ghidra/Features/Decompiler/src/decompile/cpp/consolemain.cc``

Obviously you need to [``registerProgram``](https://github.com/NationalSecurityAgency/ghidra/blob/6842712129b8da45077bb8c5049e607d685f4dea/Ghidra/Features/Decompiler/src/main/java/ghidra/app/decompiler/DecompileProcess.java#L414)

before

```java

protected void initializeProcess() throws IOException, DecompileException {

if (decompCallback == null) {

throw new IOException("Program not opened in decompiler");

}

if (decompProcess == null) {

decompProcess = DecompileProcessFactory.get();

}

else if (!decompProcess.isReady()) {

DecompileProcessFactory.release(decompProcess);

decompProcess = DecompileProcessFactory.get();

}

long uniqueBase = UniqueLayout.SLEIGH_BASE.getOffset(pcodelanguage);

XmlEncode xmlEncode = new XmlEncode();

pcodelanguage.encodeTranslator(xmlEncode, program.getAddressFactory(), uniqueBase);

String tspec = xmlEncode.toString();

xmlEncode.clear();

dtmanage.encodeCoreTypes(xmlEncode);

String coretypes = xmlEncode.toString();

SleighLanguageDescription sleighdescription =

(SleighLanguageDescription) pcodelanguage.getLanguageDescription();

ResourceFile pspecfile = sleighdescription.getSpecFile();

String pspecxml = fileToString(pspecfile);

xmlEncode.clear();

compilerSpec.encode(xmlEncode);

String cspecxml = xmlEncode.toString();

decompCallback.setNativeMessage(null);

decompProcess.registerProgram(decompCallback, pspecxml, cspecxml, tspec, coretypes,

program);

```

* @param pspecxml = string containing .pspec xml

* @param cspecxml = string containing .cspec xml

* @param tspecxml = XML string containing translator spec

* @param coretypesxml = XML description of core data-types

./Ghidra/Processors/x86/data/languages/x86.pspec

./Ghidra/Processors/x86/data/languages/x86.ldefs

./Ghidra/Processors/x86/data/languages/x86.slaspec

./Ghidra/Processors/x86/data/languages/x86.opinion

./Ghidra/Processors/x86/data/languages/x86.sla

/opt/ghidra-github/Ghidra/Processors/x86/data/languages/x86-64.pspec

cspec

tspec

coretypes

```

void RegisterProgram::rawAction(void)

ghidra = new ArchitectureGhidra(pspec,cspec,tspec,corespec,sin,sout);

ghidra->init(store);

```

## Theorems

Now, the title of this section can be puzzling, why theorems? remember when I

told you that every basic block controlling the flow of the code has a logic

condition at end? this means that a continous path from vertex \\(A\\) to vertex

\\(B\\) is practically "building" a formula using boolean conditions.

Let me step back a little to explain some maths to you

- ``SAT``: Boolean Satisfability Problem, i.e. determining if there exists an

interpretation that satisfies a given boolean formula.

- ``SMT``: Satisfability Modulo Theory, an extension of ``SAT``

- ``BMC``: Bounded Model Checking

- [Introduction to SMT with Z3](https://www.iaik.tugraz.at/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Introduction-to-SMT-with-Z3.pdf)

## Experiment with ghidra

Since I'm interested to practical applications but I want to be able to use this

mechanism directly while I'm reverse engineering code with ``ghidra``, I want a

way to "lift" the ``Pcode`` as logical expression and work on that.

It's not a difficult task, I mean, ``Pcode`` has not many instructions and it's

a tedious but doable task, for example [maat does that](https://github.com/trailofbits/maat/blob/master/src/ir/cpu.cpp#L471)

but it's ``C++`` but fortunately for me someone has done that in ``Java``, a tool named,

[GhiHorn](https://github.com/CERTCC/kaiju/tree/fbefa018eb93e4821aa9eadd7e34f073a2efde8f/src/main/java/kaiju/tools/ghihorn),

thanks to the magic of Jython I can use directly from the console since the

classes are defined as ``public``, take note that here however we are using the

``Java``'s APIs

([here](https://z3prover.github.io/api/html/namespacecom_1_1microsoft_1_1z3.html)

the documentation)

```

>>> from kaiju.tools.ghihorn.decompiler import GhiHornSimpleDecompiler

>>> from kaiju.tools.ghihorn import GhiHornifierBuilder

>>> from kaiju.tools.ghihorn.api import GhiHornApiDatabase

>>> apiDatabase = GhiHornApiDatabase(GhiHornSimpleDecompiler())

>>> hornifier = SimpleHornifier("kebab")

>>> hornifier.setDecompiler(GhiHornSimpleDecompiler())

>>> hornifier.setEntryPoint(toAddr(0x0101149))

>>> hornifier.setApiDatabase(apiDatabase)

>>> hornifier.hornify(currentProgram, ConsoleTaskMonitor())

```

```

/**

* Expressions that represent a p-code operation. They basically have the form:

*

* out = OP(in...)

*/

public class PcodeExpression implements HornExpression {

...

}

```

If I place the cursor on the ``uvar1 < 4`` block of this code

```c

int main(int argc,char **argv)

{

uint uVar1;

int jim;

uVar1 = atoi(argv[1]);

if (uVar1 < 4) {

puts("!");

}

return 0;

}

```

I can extract the logic expression from the ``Pcode``

```

>>> from kaiju.tools.ghihorn.hornifer.horn.expression import PcodeExpression

>>> currentLocation.getToken().getPcodeOp()

(unique, 0xcb80, 1) INT_LESS (register, 0x0, 4) , (const, 0x4, 4)

>>> pcode = currentLocation.getToken().getPcodeOp()

>>> expr = PcodeExpression(pcode)

>>> expr.getOperation()

uVar1@main!cast_argv < const=4

```

seems pretty ok, I want to investigate a little more, in particular I'm

interested to see if it's encoded as an **unsigned** operation

```

>>> type(expr)

>>> expr.getComponents()

array(kaiju.tools.ghihorn.hornifer.horn.expression.HornExpression, [uVar1@main!cast_argv, const=4])

>>> expr.getComponents()[0]

uVar1@main!cast_argv

>>> var = expr.getComponents()[0]

>>> var.getDataType()

kaiju.tools.ghihorn.z3.GhiHornBitVectorType@6385652a

>>> expr.getOperation().getClass()

```

and indeed, from the last line, it is!

Now I want to use it

```

>>> from kaiju.tools.ghihorn.z3 import GhiHornContext

>>> ctx = GhiHornContext()

>>> solver = ctx.mkSolver()

>>> type(solver)

>>> instance = expr.instantiate(ctx)

>>> instance

(= bVar148@main!cast_argv (bvult uVar1@main!cast_argv #x0000000000000004))

>>> type(instance)

>>> solver.add(instance)

>>> solver.check()

SATISFIABLE

>>> model = solver.getModel()

>>> model

(define-fun uVar1@main!cast_argv () (_ BitVec 64)

#x0000000000000000)

(define-fun bVar148@main!cast_argv () Bool

true)

```

Now, listen, I know that ``Java`` is shit so I'm teaching a neat trick to export

all, from ``Java``

```

>>> print solver.toString()

(declare-fun bVar145@main!array () Bool)

(declare-fun uVar1@main!array () (_ BitVec 64))

(assert (= bVar145@main!array (bvult uVar1@main!array #x0000000000000003)))

(model-add bVar145@main!array

()

Bool

(not (bvule #x0000000000000003 uVar1@main!array)))

```

you can import into ``python``

```

In [1]: import z3

In [2]: s = z3.Solver()

In [3]: s.from_string("(declare-fun bVar145@main!array () Bool)\n(declare-fun uVar1@main!array () (_ BitVec 64))\n(assert (= bVar145@main!array (bvult uVar1@main!array #x0000000000000003)))\n(model-add bVar145@main!array\n ()\n ...: Bool\n (not (bvule #x0000000000000003 uVar1@main!array)))\n")

In [4]: print(s)

[bVar145@main!array == ULT(uVar1@main!array, 3)]

```

## Ideas

- Maybe having a distribution of the input and looking for the element in the tail

of such distribution. Note here the "right" or "compliant" input is tricky:

in theory everything accepted is compliant.

- Try to build a finite state machine from the CFG

```c

struct {

size_t length;

char payload[];

} miao_t

void do_something(char* buffer, miao_t* m) {

size_t length = m->length - sizeof(m->head);

memcpy(buffer, m->payload, length);

}

```

here, with the assumption that the attacker controls the ``m`` variable in its

entirety,

the obvious vulnerability is that if ``m->length`` is less than the size in

bytes of the field ``head`` then an underflow happens.

**But** if the attacker controls the two arguments, i.e. the **two pointers**

now you have a read/write primitive :)

## Links

- [Abstract Interpretation spring 2005 course](http://web.mit.edu/afs/athena.mit.edu/course/16/16.399/www/) with slides

- [Awesome symbolic execution](https://github.com/ksluckow/awesome-symbolic-execution) github repo

- [Why Horn Formulas Matter in Computer Science: Initial Structures and Generic Examples](https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/82190596.pdf)

- [Z3 Python tutorials](https://ericpony.github.io/z3py-tutorial/)

- [SAT/SMT by example](https://sat-smt.codes/SAT_SMT_by_example.pdf)

- [Dynamic Symbolic Execution for Software Analysis](https://gtmfs2020.github.io/media/gtmfs2020_slides_Cadar.pdf)

- [LLBMC — The Low-Level Bounded Model Checker](https://llbmc.org/)

- [Constrained Horn Clauses (CHC)](https://ece.uwaterloo.ca/~agurfink/ece750t29f18/assets/pdf/07_CHC_LIA.pdf) from Automated Program Verification (APV) Fall 2018

- [Identifying Loops In Almost Linear Time](https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/316686.316687)

- [Practical Dynamic Reconstruction of Control Flow Graphs](https://homepages.dcc.ufmg.br/~fernando/publications/papers/RimsaSPE20.pdf)

- [A Survey of Symbolic Execution Techniques](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1610.00502.pdf)

- [Regular Property Guided Dynamic Symbolic Execution](https://zbchen.github.io/Papers_files/icse2015.pdf)

- [Symbolic Verification of Regular Properties](https://zbchen.github.io/Papers_files/icse2018-1.pdf)

- [ESP: Path-Sensitive Program Verification in Polynomial Time](https://web.eecs.umich.edu/~weimerw/590/reading/dls-pldi02.pdf)

- [Algorithms for Computing the Static Single Assignment Form](https://iss.oden.utexas.edu/Publications/Papers/JACM2003.pdf)

- [Efficiently Computing Static Single Assignment Form and the Control Dependence Graph](https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~pingali/CS380C/2010/papers/ssaCytron.pdf)

- [Static Program Analysis](https://cs.au.dk/~amoeller/spa/spa.pdf)

- static program analysis technique of [Abstract Interpretation](https://wiki.mozilla.org/Abstract_Interpretation) by Mozilla

- [Abstract Interpretation](https://pages.cs.wisc.edu/~horwitz/CS704-NOTES/10.ABSTRACT-INTERPRETATION.html)

- [Abstract Interpretation and Abstract Domains](https://www.dsi.unive.it/~avp/domains.pdf)

- [An abstract interpretation-based deobfuscation plugin for ghidra](https://www.msreverseengineering.com/blog/2019/4/17/an-abstract-interpretation-based-deobfuscation-plugin-for-ghidra)

- [RolfRolles/GhidraPAL](https://github.com/RolfRolles/GhidraPAL) Ghidra Program Analysis Library

- [Concrete interpretation of Chess](https://static1.squarespace.com/static/53a64cc2e4b0c63fc41a3320/t/5a94f02824a694ce120900d0/1519710249860/SBM-Concrete+Interpretation+of+Chess.pdf)

- [Abstract intepretation of Chess](https://static1.squarespace.com/static/53a64cc2e4b0c63fc41a3320/t/5a94f03853450a67004c973c/1519710266003/SBM-Abstract+Interpretation+of+Chess.pdf)

- Be a binary rockstar ([video](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jqyoDlGyao4))

- [Look out! Divergent representations are everywhere!](https://blog.trailofbits.com/2022/11/10/divergent-representations-variable-overflows-c-compiler/)

- [BINSEC](https://binsec.github.io/) binary code analysis for security

- [Proving the security of software-intensive embedded systems by abstract interpretation](https://hal.inria.fr/tel-03127921/document), PhD thesis by Marc Chevalier where a more realistic

semantics of C is defined.

- [Finding JIT Optimizer Bugs using SMT Solvers and Fuzzing](https://www.pypy.org/posts/2022/12/jit-bug-finding-smt-fuzzing.html) in ``PyPy``.

- [gtirb](https://github.com/GrammaTech/gtirb) Intermediate Representation for Binary analysis and transformation

- [ddisasm](https://github.com/GrammaTech/ddisasm) A fast and accurate disassembler

- [Ghidraton](https://www.mandiant.com/resources/blog/ghidrathon-snaking-ghidra-python-3-scripting), Snaking Ghidra with Python 3 Scripting

- [Hyperproperties](https://www.cs.cornell.edu/fbs/publications/Hyperproperties.pdf), paper by Michael R. Clarkson and Fred B. Schneider

- [IKOS](https://github.com/NASA-SW-VnV/ikos) Static analyzer for C/C++ based on the theory of Abstract Interpretation by NASA ([slide](https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20170009851/downloads/20170009851.pdf))

- [Proving the correctness of multiprocess programs](https://lamport.azurewebsites.net/pubs/proving.pdf), papers where "liveness" and "safeness" were defined

- [“Static Analysis by Abstract Interpretation and Decision Procedures”](https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01102418/document) PhD thesis by Julien Henry and [PAGAI](https://pagai.gricad-pages.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/), a tool which does Path Analysis for invariant Generation by Abstract Interpretation